- Home

- Roy J. Snell

The Phantom Violin Page 9

The Phantom Violin Read online

Page 9

CHAPTER IX THE CALL OF THE GYPSIES

The following day was bright and clear. The waters of Old Superior wereas blue as the sky. Even the wreck took on a scrubbed and smilingappearance.

"As if we were all prepared to shove off for one more voyage," Jeannesaid with a merry laugh.

As soon as the sun had dried the deck, Jeanne and Greta spread blanketsand, stretching themselves out like lazy cats, prepared for a glorioussun bath.

It was a drowsy, dreamy day. In the distance a dark spot against theskyline was Passage Island where on stormy nights a search-light, ahoarse-hooting fog horn and a whispering radio warned ships of danger.

All manner of ships pass between Isle Royale and Passage Island. Theywere passing now, slowly and, Jeanne thought, almost mournfully. Firstcame a dark old freighter with cabins fore and aft, then a tugboat towinga flat scow with a tall derrick upon it, and after these, all paintedwhite and with many flags flying, an excursion boat. And then, rearedover on one side and scooting along before the wind, a sailboat.

Just to lie in the sun and watch this procession was life enough forJeanne and Greta. Not so Florence. She was for action. Dizzy needed fish.She would row over to the shoals by Blake's Point. There she would trollfor trout.

The water about Blake's Point is never still. It is as if some greatgreen serpent of the sea lies stretched among the rocks and keeps it inperpetual motion by waving his tail. It was not still when Florencearrived.

"Just right," she whispered, as if afraid the fishes might hear. "Roughenough for a little excitement, and no real danger."

Casting a shining lure into the water, she watched the line play out asshe rowed.

A big wave lifted her high. Still the line played out. The boat sank low.She checked the line. Then, watching the rocks that she might not cometoo close and snag them, she rowed away.

For some time she circled out along the shoals, then back again. She hadbegun to believe there were no fish, and was musing on other things,phantom violins, black schooners, gray wolves, Old Uncle Ned, when, witha suddenness that was startling, her reel began to sing.

Dropping her oars, she seized the pole and began reeling in rapidly. Nextmoment she tossed a fine three pound trout into her boat. "You get 'emquick or not at all," Swen had said to her. She had got this one "quick."

An hour later four fine trout lay in the stern of her boat. "Enough," shebreathed. "We eat tonight, and so does Dizzy."

The day was still young. She had not meant to visit Duncan's Bay, but nowthe place called to her.

Swen's short, powerful rifle lay in the prow of her boat. Why had shebrought it? Perhaps she could not tell. Now she was glad it was there.

"Go ashore on Duncan's Bay," she told herself. "Go hunting phantoms and,perhaps, a gray wolf or two. Wouldn't mind shooting them, the murderers,not a bit!"

It was a strange wolf she was to come upon in the forest that day.

With corduroy knickers tucked in high laced boots, a flannel shirt openwide at the neck, and a small hat crammed well down on her head, thisstalwart girl might have been taken for a man as, rifle under arm, shetrudged through the deep shadows of the evergreen forest covering theslope of Greenstone Ridge.

That she was in her element was shown by the spring in her footstep, theglad, eager look in her eyes.

"Life!" she breathed more than once. "Life! How marvelous it is!

"'I love life!'" She hummed the words of a song she had once heard.

"Life! Life!" she whispered. Here indeed was life in its most primitiveform. At times through a narrow opening she caught a glimpse of graygulls soaring like phantom ships over the water. To her ears came thelong, low whistle of some strange bird. She was not surprised when shefound herself standing face to face with a magnificent broad-antleredmoose. She stood quite still.

Great eyed, the moose stared at her. A sound to her right caught herattention. She looked away for an instant. When her gaze returned to thespot where the monarch of the forest had stood, he had vanished.

"Gone!" she exclaimed low. "Gone! He was taller than a man, yet hevanished without a sound! How strange! How sort of wonderful! But Iwonder--"

But there was that sound from below. Snapping of twigs and swishing ofbranches. No moose that. She would see what was down there.

She did see, and that almost at once. A few silent steps, and she cameupon him--a man. He was standing at a spot where a break in theevergreens left a view of Duncan's Bay.

He was looking straight ahead. On his face was a savage, hungry look.Only the night before the girl had seen that same look in the eyes of awolf.

She was not long in learning the reason. In plain view through thatnarrow gap was the patriarch of his tribe, the moose she had saved fromthe wolf.

"But why that look?" She was puzzled, but not for long. In the hands ofthat man was a rifle. An ugly smile overspread his face. His teeth shoneout like fangs as he lifted the rifle and took deliberate aim at themoose.

She recalled Swen's words: "Isle Royale is a game preserve. You will notbe allowed to kill even a rabbit."

"This man is a poacher." Her mind, always keen, worked quickly. "I cansave the moose, and I will!"

Swinging her own rifle into position, she fired well over the heads ofman and moose. The shot rang out. The startled moose fled.

And the man? She did not pause to see. Like a startled rabbit she wentdodging and gliding back and forth among the evergreens. In her mind,repeated over and over, was the question, "Did he see me? Did he see me?"

* * * * * * * *

After a long and glorious sun bath followed by a delicious lunch servedon deck, Jeanne and Greta sat for a long time staring dreamily at thesea. Then Jeanne, throwing off her velvet robe, stood up, slim andstraight, on the planked deck.

"Wonder if I can have forgotten," she murmured. Then, seizing atambourine, she began a slow, gliding and weaving motion that, like somebeautiful work evolved from nothing by the painter's skillful hand,became a fantastic and wonderful dance.

For a full quarter hour Greta sat spellbound. She had seen dancing, butnone like this. Now the tambourine was rattling and whirling over thelittle French girl's head, and now it lay soundless on the deck. Now thedancer whirled so fast she was but a gleam of white and gold. And now herarms moved so slowly, her body turned so little, she might have seemedasleep.

"Bravo! Bravo!" cried Greta. "That was marvelous! Where did you learnit?"

"The gypsies taught me." Dropping upon the deck, Jeanne rolled herself ina blanket like a mummy.

"People," she said slowly, "believe that all gypsies are bad. That is notso. One of the very great preachers was a gypsy--not a convertedgypsy--just a gypsy.

"Bihari and his wife were my godparents in France. They were wanderinggypsies, but such wonderful people! They took me when I had no home. Theygave me shelter. I learned to dance with my bear, such a wonderful bear.He is dead now, and Bihari is gone. I wish they were here!"

Next moment she went rolling over and over on the deck. Springing like abeautiful butterfly from a cocoon, she whirled away in one more riotousdance.

It was in the midst of this that a strange thing happened. Music came tothem from across the waters--wild, delirious music.

Jeanne paused in her wild dance. For a space of seconds she stood theredrinking in that wild glory of sound.

Then, as if caught by some spell, she began once more to dance. And herdance, as Greta expressed it later, was "like the dance of the angels."

"Greta," Jeanne whispered hoarsely when at last the music ceased and shethrew herself panting on the deck, "that is gypsy music! No others canmake music like that. There is a boat load of gypsies out there byDuncan's Bay."

"Yes, yes!" Greta sprang to her feet. "See! It is a white boat. It isjust about to enter the Narrows. Perhaps Florence will see it."

"Florence--" There was a note of pain in Jeanne's voice. "Florence h

asthe boat. I cannot go to them. Perhaps I shall not see them--my friends,the gypsies. And they make music, such divine music!"

"Music--divine music," Greta whispered with sudden shock. "Can one ofthese have been my phantom violinist?

"No," she decided after a moment's contemplation, "that was different.None of these could have played like that."

"It is the call!" Jeanne cried, springing to her feet and stretching herarms toward the distant shore. Fainter, more indistinct now the musicreached their ears. "The gypsies' call! I have no boat. I cannot go."

On the Yukon Trail

On the Yukon Trail Wings over England

Wings over England Johnny Longbow

Johnny Longbow Sally Scott of the WAVES

Sally Scott of the WAVES The Secret Mark

The Secret Mark Betty Leicester's Christmas

Betty Leicester's Christmas The Firebug

The Firebug Minnie Brown; or, The Gentle Girl

Minnie Brown; or, The Gentle Girl Jack the Hunchback: A Story of Adventure on the Coast of Maine

Jack the Hunchback: A Story of Adventure on the Coast of Maine The Silent Alarm

The Silent Alarm The Arrow of Fire

The Arrow of Fire The Magic Curtain

The Magic Curtain The Crystal Ball

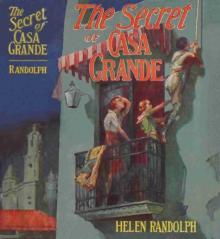

The Crystal Ball The Secret of Casa Grande

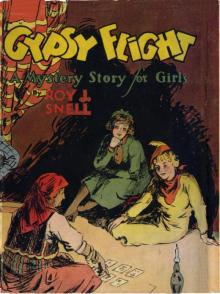

The Secret of Casa Grande Gypsy Flight

Gypsy Flight The Mystery of Carlitos

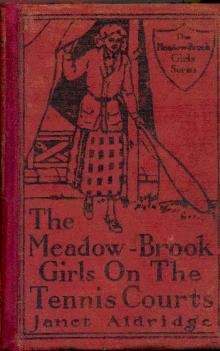

The Mystery of Carlitos The Meadow-Brook Girls on the Tennis Courts; Or, Winning Out in the Big Tournament

The Meadow-Brook Girls on the Tennis Courts; Or, Winning Out in the Big Tournament Witches Cove

Witches Cove Riddle of the Storm

Riddle of the Storm Forbidden Cargoes

Forbidden Cargoes Green Eyes

Green Eyes Sign of the Green Arrow

Sign of the Green Arrow The Red Lure

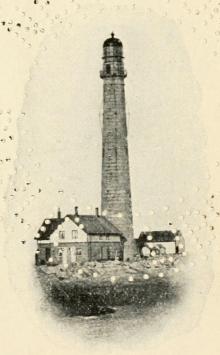

The Red Lure The Light Keepers: A Story of the United States Light-house Service

The Light Keepers: A Story of the United States Light-house Service A Ticket to Adventure

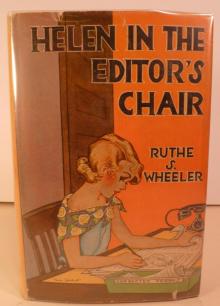

A Ticket to Adventure Helen in the Editor's Chair

Helen in the Editor's Chair Blue Envelope

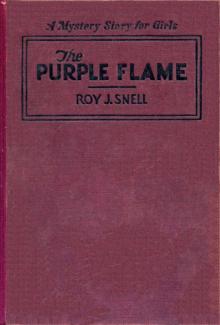

Blue Envelope The Purple Flame

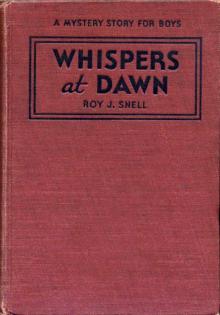

The Purple Flame Whispers at Dawn; Or, The Eye

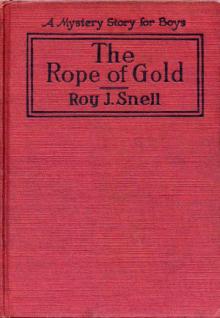

Whispers at Dawn; Or, The Eye The Rope of Gold

The Rope of Gold Crossed Trails in Mexico

Crossed Trails in Mexico The Shadow Passes

The Shadow Passes Red Dynamite

Red Dynamite Blue Grass Seminary Girls on the Water

Blue Grass Seminary Girls on the Water The Cruise of the O Moo

The Cruise of the O Moo