- Home

- Roy J. Snell

Forbidden Cargoes

Forbidden Cargoes Read online

Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Rod Crawford, Dave Morganand the Online Distributed Proofreading Team athttps://www.pgdp.net

_Mystery Stories for Boys_

Forbidden Cargoes

_By_ ROY J. SNELL

The Reilly & Lee Co. Chicago New York

_Printed in the United States of America_

_Copyright, 1927_ by The Reilly & Lee Co. _All Rights Reserved_

CONTENTS

CHAPTER PAGE I A Strange Message 9 II An Underground Sea 29 III A Strange Dark Room 47 IV Johnny Thompson in Jail 58 V Tottering Walls 68 VI An Earthquake Within a Cave 74 VII Johnny Wins a Friend 85 VIII An Ancient Castle in Ruins 96 IX Creeping Shadows 108 X Camp Smoke 117 XI Battling Against Odds 131 XII Destruction 152 XIII A Thousand Pearls 166 XIV Hope Springs Eternal 179 XV Unseen Foes 192 XVI In Battle Array 201 XVII Pant's Problem Increases 214 XVIII Two Blade Johnny 221 XIX The Unwilling Guest 230 XX Hail and Farewell 247 XXI On the Trail of the Pearls 254 XXII A Startling Revelation 263 XXIII Treasure at Last 274

Forbidden Cargoes

CHAPTER I A STRANGE MESSAGE

In a plain board shack with a palm thatched roof which had the CaribbeanSea at its front and the Central American jungle at its back, a slim,stooping sort of boy, with eyes that gleamed out of the dark cornersexactly like a tiger's, paced back and forth the length of a long, lowroom. His every motion suggested a jaguar's stealth.

It was Panther Eye, a boy who was endowed with a cat's ability to see inthe dark, and who spent much of his young life in India and othertropical lands. He also found himself quite at home in Central America.Nevertheless, at this moment he was in deep trouble.

The palm thatched shack boasted but one room. As the boy paced themahogany floor of this room he passed a desk of roughly hewn rosewood. Asmall steel safe stood in one corner, the door slightly ajar. Before iton the floor lay a litter of papers, a few bundles of letters and asizeable roll of currency. The boy paused to consider this litter.

"It was the map they wanted," he told himself. "Easy enough to see that.They didn't even look at the money, nearly a thousand dollars. The map!They knew we could do nothing without the map. The dirty dogs! If onlyJohnny Thompson were here!" Again he paced the floor.

What was to be done? His thoughts were in a tangle. The thieves who hadbroken into the safe were now well away in the jungle. There was no timeto be lost. He'd catch them, he was sure of that. A jaguar couldn'tescape him, much less a man. Yet the map might be destroyed. Without itnothing could be accomplished. Thousands were at stake, the treasure of alifetime. And some one dearer to Pant than life itself was scheduled tolose. All day in that stuffy office he had waited for Johnny. Now eveningwas near.

"If only Johnny would come!" he repeated.

Had he but known it, his good pal, Johnny Thompson, was some threehundred miles away. What was more, he was behind iron bars in a stoutstone jail. But this Pant could not know, so he continued to pace thefloor.

As the first long shadow of a palm darkened the window he suddenly spranginto action. Throwing up the lid of a rough chest, he tossed out amiscellaneous assortment of articles, some small oilcloth wrappedpackages, a black box, some fibre trays, a few articles of clothing and acurious instrument of iron. These he packed carefully in a kit bag, thenclosed the chest.

Seating himself at the desk in the corner, he began pecking at a smallportable typewriter. He destroyed four half written sheets before he didone to suit him. The following is what appeared on the one he at lastweighted down upon the desk:

/9*::6 5*3 ;@0 8$ -9:3 5*3 $0@:8@4%$ *@'3 85 8 @; -98:- 8:59 5*3 /7:-#3 @!534 85 8 28## -35 85 :3'34 !3@4 #99= 975 !94 @ $0@:- 8@4% :@;3% %8@( *3 8$ @ %3'8# :3'34 547$5 :94 '3#83'3 *8; !94 @ ;9;3:5 -99% #7?= 0@:5

"There!" he sighed as he turned from the desk. "If Johnny Thompsondoesn't make that out right away he won't be coming up to myexpectations. And if any of these blacks and browns and whites thatinfest this waterfront can read it, I take off my hat to 'em."

Turning about, he slung the strap of his kit bag across his shoulder andleaving the cabin, disappeared into the gathering night and the jungle.

Some hours later he might have been found crouching close to the side ofa bamboo hut at the heart of the jungle.

His hands trembled as he unwrapped a water-proof package. They trembledstill more as he poured a gray powder from the package to a narrow Vshaped piece of iron. A little of the powder was spilled over the sideand, sinking into the deep bed of tropical moss, was lost forever.

"Won't do," he told himself, stiffening his shoulders. "I've got to gethold of myself. If I don't keep cool I'll make a mess of it and like asnot get caught in the bargain.

"Caught by those Spaniards in the heart of the jungle!" He shuddered atthe thought. "Caught. And what then?" He dared not think.

"No!" His resolve was strong. "They shall not get me, and I shallsucceed. I must!" His face grew tense.

At that he went ahead with his task. Having spread the gray powder evenlyalong the iron trough, he ran a small black fuse half through it, thengave the fuse five turns about it. When he had finished, the lower end ofthe fuse hung some six inches below the trough.

"There!" he sighed.

A half hour later found him still crouching at the back of that cabin.This shelter, for it was little more, was of the sort common to theCentral American jungle. In its construction not a board and not a singlenail was used. A number of cohune nut palms had been felled. Their greatfronds had been stripped. The fibre stripped from the stems had beenpiled in a heap, the stems themselves in another heap. Crotched mahoganylimbs were fastened together with tie-tie vines. This made a frame.Rafters were added. The bamboo leaf fibre had been laid carefully intiers over the rafters. This made a perfect roof. After that the ten footstems of a great number of leaves were fastened side by side in aperpendicular position to form walls. When this was completed the housewas ready to be occupied.

The cracks between the upright bamboo stems forming the walls were wide.A faint light shone through these cracks, and through them the boy couldsee all that went on within. All this interested him, but he was filledwith a fever of impatience. He had come to act, not to listen.

Two dark-faced Spaniards sat in the center of the room. Two black bushmenlay sprawled upon the dirt floor. Before them, suspended upon a bambooframe, was a map. The map, some four feet across, showed certain boundar

ylines, creeks and rivers. There were spots that had been done in blue.Still others were crisscrossed by pen lines, while larger portions wereleft white. The figure of one Spaniard hid part of the map.

"Ah!" The boy breathed an inaudible sigh of relief as the man moved,allowing a full view of the map. "Now, if only I can do it!"

With the greatest care, he thrust the triangle of steel upon which thepowder rested through a crack. Next he adjusted a small black box beforethe crack, but lower down. Then, with a hand that still trembled slightlyin spite of his efforts at self control, he drew a sulphur match across adry bit of wood.

The sulphur fumes rose and floated through the cracks. At the same timethere came the faint sput-sput-sput of a burning fuse. One of theSpaniards arose and sniffed the air. He spoke a word to a companion. Theyturned half about. And still the fuse burned. Shorter and shorter itbecame, closer and closer to the powder.

The boy's heart was in his throat. Was the whole affair to be spoiled bya whiff of sulphur or a fuse that burned too long?

"If they rise, if they block the view," he thought, "then all will be--"

But no, they settled back. The whiff of sulphur had passed. But what wasthis? A black man jumped. Had the smell of burnt powder reached him? Hadthe sput-sput of the fuse reached his sensitive ear?

Whatever it was, it came too late. Of a sudden there sounded out a loudboom, and at once, for a fraction of a second, the whole place, cabin,bamboo trees, and the surrounding jungle was lighted as with a moment'sreturn of the sun. Then came sudden and complete darkness.

Within was noise and confusion. A bushman had overturned the candle. Ithad gone out. In fright and rage at an unknown phenomenon, an unseenenemy, the men fought their way to the door, then out into the night.Before this happened, however, the boy, hugging his precious black boxunder his arm, had lost himself in the jungle.

As we have said, this boy had lived much in the tropics. The CentralAmerican jungle was not new to him. Deep secrets of these wilds had cometo him by day and by night.

With the startled cries of Spaniards and bushmen ringing in his ears, hemade his way swiftly, silently down a narrow deer path to a spot where hehad hidden his canvas bound kit bag.

Thrusting his black box deep within the bundle, still without a light, hemade his way swiftly forward until the shouts died away in the distance.

"If only it is a success!" he thought with a sigh as he paused to adjusthis pack.

Coming at last to a narrow stream he cast a few darting glances abouthim. The jungle here was new to him, yet the bubbling stream, the moss onthe tree trunks, the tossing leaves far above him, told him all he neededto know.

Turning sharply to the right, he followed a narrow trail up the windingbank of the stream.

He had been traveling steadily up this stream for more than three hourswhen he came upon a place where the stream was a roaring young cataract,tumbling down a series of little falls. This was the thing he hadexpected. He was sleepy. The night was far spent. In his pack was amosquito bar canopy and a light, strong hammock, woven from linen thread.With these he could quickly build a safe wilderness home. In the lowswamp land, where malaria and mosquitoes lurked, he did not dare to camp.

There were wild creatures in all this jungle; crocodiles, droves of wildpigs, great boa constrictors and golden coated jaguars. For this boy allthese held little terror. But the swamps were not for him. The higherslopes of the narrow peninsula offered fresher air, and cooling breezesthat lull one to sleep.

"Sleep," he whispered to himself, "and after that a dark place."

At that moment the moonlight, falling through an open space among thetrees and spreading a yellow gleam upon the trail, showed him that whichbrought him up short. In a damp spot at the base of a rock werefootprints, the marks of a slim foot clad in sandals, and stranger thanthis in so wild a spot, the marks of a leather shoe.

"Huh!" He stood for a moment in perplexity.

One who knows the jungle is seldom surprised at what he finds there. Pantwas surprised. This portion of the jungle was new to him. "Twenty milesfrom the coast," he murmured. "How strange!"

More was to follow. He had not gone a hundred yards farther before hecame upon a well-beaten road. A little beyond this spot, in the midst ofa broad clearing, half hidden by stately royal palms, gleaming white inthe moonlight, was a long, low stone house which in this land mightalmost pass for a mansion.

Pausing, he stood there in the moonlight, staring and irresolute. It hadall come to him in a flash.

"The last of the Dons," he said to himself. Something akin to awe creptinto his tone. "I had forgotten."

"But what now?" he asked himself a moment later. "The jungle or this?"

In the end he chose the castle before him. "Might be a dark place upthere somewhere, an abandoned cellar perhaps," was his final comment.

Having chosen a secluded spot at the side of the trail where he mighthang his hammock and spread his canopy to sleep the rest of the nightthrough, he went quickly to rest.

"I have heard that they are friendly, and honorable Spaniards. There aresuch, plenty of them. I'll risk it. I--"

At that, with the breeze swaying his hammock, he fell asleep.

The sun was sending its first yellow gleams among the palms when heawoke. For a time, with the damp sweet odor of morning in his nostrils,he lay there thinking.

A strange mission had brought him into the jungle. This strange boy hadgrown up with little or no knowledge of blood relations. His father andmother were but a dim, indistinct memory. They had passed from his life;he did not know exactly how. No cozy home fireside had gleamed for him.He had gone out into the world with an unanswered longing for some onewhom he might think of as a kinsman. Bravely he had fought his waythrough alone. When Johnny Thompson came into his life and remained thereto become his inseparable pal, life had been more joyous. Yet ever thereremained a haunting dream that somehow, somewhere in his wild wanderingshe would come upon one who bore his name, who could give him thetraditions of a family and of a past.

Strangely enough, it had been at the edge of the Central American junglethat he came upon this person of his dreams. While walking upon the coralbeach he had met a stately, white-haired old man who had the militarybearing of a colonel.

In this old man he had found a friend. Little enough was left of thefortunes which from time to time had come to the venerable southerner.But such as he had he shared unsparingly with the young stranger who hadcome so recently from the land of his birth; for Colonel Longstreet, asthe patriarch styled himself, though now for more than sixty years aresident of Central America, had fought valiantly for a lost cause whenthe Gray stood embattled against the Blue in that long and terriblestruggle, the Civil War.

Broken hearted because of the outcome of the war, he had left his nativestate of Virginia and had come to Central America. His life had beenfurther embittered by the early death of his wife. His only child, a boyof ten, had been sent back to Virginia while he struggled on, wresting afortune from the jungle.

Life in Central America is one gamble after another. Longstreet hadplayed in every game. He had always won, in the end to lose again.Fortunes in sugar, bananas and mahogany had been his. Sudden drops inprices, a revolution, the dread Panama disease, had cost him all ofthese. Now he was playing a last, lone card. Influential friends wereendeavoring to secure for him a concession for gathering chicle on broadtracts of Government land.

This was the state of affairs when Pant had made his acquaintance. Hardlyhad their acquaintance ripened into deep friendship when they made thesudden and startling discovery that Pant was the son of the boy who hadbeen sent back by Colonel Longstreet to Virginia, that Colonel Longstreetwas none other than Pant's grandfather. From that time forth the strangeboy, who had longed for so many lonely years for one of kin, became theold man's devoted slave.

There was need enough at the present time for such devotion.

Fortune had seemed to smile at last. Through the influence

of hisfriends, a concession from the British Government for gathering chiclehad come from England to Colonel Longstreet.

"Chicle, as you may know," the old man had smiled, as he told Pant of it,"is the basis of all good chewing gum. Were it not for the great Americangame of chewing it wouldn't be worth a red cent. As it is, with onecompany importing two million dollars worth a year and other smallercompanies competing and yelling for more, there's a fortune in it. Thereis a net profit of twenty-five cents a pound on chicle. With properworking, our tract should yield between twenty-five and fifty thousandpounds a year."

With the writings of agreement had come a map showing the exactboundaries of the Government tract they had leased. To the right andabove this tract was shown on the map the holdings of a powerful Americanorganization. To the left were tracts leased by an unprincipled Spaniardnamed Diaz.

Two days after news of the fortunate concession had gone about the littlecity, Diaz had appeared in the Colonel's small office. He offered aridiculously low price for the concession. His offer was rejected. He wastold that the owner meant to work the concession. He shrugged hisshoulders and said:

"No get the men."

The old man had straightened to his full height as he informed theSpaniard that he had men who could be depended upon to go anywhere, to doanything. They had worked with him and knew the honor that lay behind theLongstreet name.

Diaz had begged, entreated, stormed, threatened, then in a rage had leftthe office.

Two days had passed. On the third day Pant had come to the office only tofind the safe looted, the map gone.

"What can we do?" he asked. "We know Diaz has it, but we can't prove it."

"We cannot," the old Colonel had agreed. "Nor is there a chance ofgetting another before it is too late. The bleeding season for chiclebegins with the first rainfall. To begin without a map is to courtdisaster. With a big and jealous American company on one side of us and acrooked Spaniard on the other, we are between the rocks and the tide. Weare sure to encroach upon one or the other. And if we do, it will takeall we have to fight their claims. It looks like defeat." He had cuppedhis hands and had stared gloomily at the sea.

"Wait," Pant had said. "Johnny Thompson will help us out. Give us alittle time. We'll find the map. Leave it to us."

Johnny Thompson, as you already know, could not help. He was not there.Two days before he had gone up the Stann Creek Railway. He had notreturned. He was in jail. Pant had been obliged to go it alone. "And nowin this short time," he told himself, "I have located the map here in theheart of the jungle. No, I haven't got it. That couldn't be done withoutbloodshed. But I have its equivalent, I hope.

"A dark place!" he exclaimed. "I must find a spot that is absolutelydark."

As he sprang from his hammock he paused to listen. Some one was singing.In a clear girlish voice there came the words of a quaint old Spanishsong.

As he parted the branches he saw a plump Spanish girl, with a round faceand sober brown eyes, tripping barefoot down the path. Balanced on herhead was a large stone jar.

"Going for the morning water," the boy told himself. "How like those oldBible pictures it all is!"

Twenty minutes later he found himself within the white walls of thatancient and mysterious castle, which had a few hours before loomed sowonderfully out of the night.

On the Yukon Trail

On the Yukon Trail Wings over England

Wings over England Johnny Longbow

Johnny Longbow Sally Scott of the WAVES

Sally Scott of the WAVES The Secret Mark

The Secret Mark Betty Leicester's Christmas

Betty Leicester's Christmas The Firebug

The Firebug Minnie Brown; or, The Gentle Girl

Minnie Brown; or, The Gentle Girl Jack the Hunchback: A Story of Adventure on the Coast of Maine

Jack the Hunchback: A Story of Adventure on the Coast of Maine The Silent Alarm

The Silent Alarm The Arrow of Fire

The Arrow of Fire The Magic Curtain

The Magic Curtain The Crystal Ball

The Crystal Ball The Secret of Casa Grande

The Secret of Casa Grande Gypsy Flight

Gypsy Flight The Mystery of Carlitos

The Mystery of Carlitos The Meadow-Brook Girls on the Tennis Courts; Or, Winning Out in the Big Tournament

The Meadow-Brook Girls on the Tennis Courts; Or, Winning Out in the Big Tournament Witches Cove

Witches Cove Riddle of the Storm

Riddle of the Storm Forbidden Cargoes

Forbidden Cargoes Green Eyes

Green Eyes Sign of the Green Arrow

Sign of the Green Arrow The Red Lure

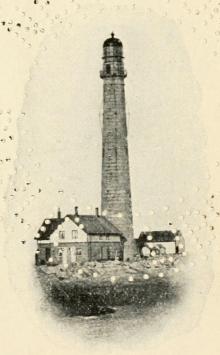

The Red Lure The Light Keepers: A Story of the United States Light-house Service

The Light Keepers: A Story of the United States Light-house Service A Ticket to Adventure

A Ticket to Adventure Helen in the Editor's Chair

Helen in the Editor's Chair Blue Envelope

Blue Envelope The Purple Flame

The Purple Flame Whispers at Dawn; Or, The Eye

Whispers at Dawn; Or, The Eye The Rope of Gold

The Rope of Gold Crossed Trails in Mexico

Crossed Trails in Mexico The Shadow Passes

The Shadow Passes Red Dynamite

Red Dynamite Blue Grass Seminary Girls on the Water

Blue Grass Seminary Girls on the Water The Cruise of the O Moo

The Cruise of the O Moo