- Home

- Roy J. Snell

The Crystal Ball Page 8

The Crystal Ball Read online

Page 8

CHAPTER VIII A VISION FOR ANOTHER

That same afternoon Florence met Sandy at the door of his glass box."Are--are you leaving?" she asked in sudden consternation. "I didn't getmy story in."

"Oh, that's O. K." Sandy, who was small, young, red-haired and freckled,threw back his head and laughed. "I did it for you. It's gone to press.Remember that psychoanalyst who wears some sort of a towel wrapped roundhis head and claims he is a Prince of India?"

"Oh, yes. He was funny--truly funny. And he wanted to hold my hand."Florence showed her two large dimples in a smile.

"Yes. Well, I did him for you. So! Come on downstairs for a cup ofcoffee."

"Sure." Florence grinned. She was not on a diet and she was ready forjust one more cup of coffee any time. Besides, she wanted to tell Sandyabout her latest finds, Madame Zaran, June Travis, and the crystal ball.

"It's the strangest thing," she was saying fifteen minutes later as,seated in a remote corner of the cafeteria maintained for employees only,she looked at Sandy over a steaming cup of coffee. "I gazed into thecrystal and, almost at once, I began seeing things!"

"What did you see?" There was a questioning look on Sandy's freckledface.

"Trees, evergreen trees." Florence's eyes became dreamy. "Trees and darkwaters, rocks--the wildest sort of place in the great out-of-doors."

"And then?"

"And then it all changed. I saw the same trees, rocks and waters coveredwith ice and snow."

"That surely _is_ strange!" The look on Sandy's face changed. "You musthave been seeing things for me."

"For you?" The girl's eyes opened wide.

"Absolutely." Sandy grinned. "You see, they're trapping moose on IsleRoyale, and--"

"Isle Royale!" Florence exclaimed. "I've been there, spent a whole summerthere. It's marvelous!"

"Tell me about it." Sandy leaned forward eagerly.

"Oh--" Florence closed her eyes for a space of seconds. "It--why it'swild and beautiful. It's a big island, forty miles long. It's all rocksand forest primeval. No timber has ever been cut there. And there arenarrow bays running back two miles where, early in summer, marvelous biglake trout lurk. You put a spoon hook on your line and go trolling. Youjust row and row. You gaze at the glorious green of birch and balsam,spruce and fir; you watch the fleecy clouds, you feel the lift and fallof your small boat, and think how wonderful it is just to live, whenZing! something sets your reel spinning. Is it a rock? You grab your poleand begin reeling in. No! It moves, it wobbles. It is a fish.

"Ten yards, twenty, thirty, forty you reel in. There he is! What abeauty--a ten pounder. You play him, let out line, reel in, let out, reelin. Then you whisper, 'Now!' You reel in fast, you reach out and up, andthere he is thrashing about in the bottom of your boat. Oh, Sandy! You'lllove it! Wish I could go. Next summer are you going?"

"Next week, most likely."

"Next week! Why, it's all frozen over. There are no boats going therenow."

"No boats, but we'll take a plane, land on skiis. You see," Sandyexplained, "our nature editor has gone south. Now this moose-trappingbusiness has come up and our paper wants a story. The thing has beendumped in my lap. I'll probably have to go."

"Oh!" The big girl's face was a study. She loved the wide out-of-doorsand all wild, free places. Isle Royale must be glorious in winter. "WishI could go along! But I--I can't."

"Why not?" Sandy asked.

"I've got this girl, June Travis, on my hands. And, unless something isdone, I'm afraid it will turn out badly."

"June Travis?" Sandy stared.

"Yes. Didn't I tell you? But of course not. It's the strangest, mostfantastic thing! I should have told you that first, but of course, likeeveryone else, I was most interested in my own poor little experience."

"Tell me about it."

Florence did tell him. She told the story well, about June gazing intothe crystal ball, the moving figures in that ball, June's fortune whichshe was soon to possess, the voodoo priestess and all the rest. She toldit so well that Sandy's second cup of coffee got cold during the telling.

"I say!" Sandy exclaimed. "You _have_ got something on your hands. Lookout, big girl! They may turn out too many for you. My opinion is that allfortune tellers are fakes, and that the biggest of them are crooked anddangerous, so watch your step."

"Oh, I know my way around this little town," Florence laughed. "And nowallow me to get you a fresh cup of coffee."

"Sandy," Florence said a moment later, "the little French girl, PetiteJeanne, was with me on Isle Royale. She'd like to hear all about yourproposed trip to the island. We may be able to think up some facts thatwill be a real help to you. Why don't you come over to our studio fordinner tomorrow night? I'm sure Miss Mabee would be delighted to haveyou."

"All right, I'll be there. How about your gypsy girl friend preparing achicken for us, one she has caught behind her van, on the broad highway?"

"Her van has vanished, much to her regret," Florence laughed. "We'll havethe chicken all the same."

"And about this story of the crystal ball," Sandy asked as they preparedto leave the cafeteria. "Shall I run that tomorrow?"

"Oh, no!" Florence exclaimed in alarm. "Not yet. I want to dig deeplyinto that. I--I'm hoping I may find something truly magical there."

"Well, don't hope too much!" Sandy dashed away to make one more"dead-line."

That had been an exciting day for the little French girl. After she hadcrept beneath the covers in her studio chamber at ten o'clock that night,she could not sleep. When she closed her eyes she saw a thousand faces.Old, wrinkled faces, pinched young faces and the half greedy, halfhopeless faces of the middle-aged. All that Maxwell Street had been asshe danced so madly for the prize that meant so little to her and so muchto another.

"Life," she whispered to herself, "is so very queer! Why must we alwaysbe thinking of others? Life should not be like that. We should be free toseek happiness for ourselves alone. Happiness! Happiness!" she repeatedthe word softly. "Why should not happiness be our only aim in life? Tosing like the nightingale, to dart about like a humming-bird, to dancewild and free like the fairies. Ah, this should be life!"

Still she could not sleep. It was often so. It was as if life were toothrilling, too joyous and charming to be spent in senseless sleep.

Slipping from her bed, she drew on heavy skating socks and slippers,wrapped herself in a heavy woolen dressing gown; then slipping silentlyout of her room, felt about in the half darkness of the studio until shefound the rounds of an iron ladder. Then she began to climb. She had notclimbed far when she came to a small trap door. This she lifted. Havingtaken two more steps up, she paused to stare about her. Her gaze sweptthe surface of a broad flat roof, their roof.

"Twelve o'clock, and all's well," she whispered with a low laugh. Theroof was silent as a tomb. She stepped out upon the roof, then allowedthe trap door to drop without a sound into its place. She was now at thetop of her own little world.

And what a world on such a night! Above her, like blue diamonds, thestars shone. Hanging low over the distant dark waters of the lake, themoon lay at the end of a path of gold.

Here, there, everywhere, lights shone from thousands of windows. Howdifferent were the scenes behind those windows! There were windows ofhomes, of offices, of hospitals and jails. Each hid a story of life.

So absorbed was the little French girl in all these things as she satthere in the shadow of a chimney, she did not note that a trap door ahundred feet away had lifted silently, allowed a dark figure to pass,then as silently closed. Had she noted this she must surely have thoughtthe person some robber escaping with his booty. She would, beyond doubt,have fled to her own trap door and vanished.

Since she did not see the intruder upon her reveries, she continued todrink in the crisp fresh air of night and to sit musing over thestrangeness of life.

Some moments later she was startled by one long-drawn musical note, itseemed to have com

e from a violin, and that not far away. Before shecould cry out or flee, there came to her startled ears, playedexquisitely on a violin, the melodious notes of _O Sole Mio_.

To her vexation and terror, at that moment the moon passed behind a cloudand all the roof was dark. Still the music did not cease.

Awed by the strangeness of it all, captivated by that marvelous musicplayed in a place so strange, Jeanne sat as one entranced until the lastnote had died away.

"There, my pretty ones!" said a voice with startling distinctness, "howdo you like that? Not so bad, eh?"

There was something of a reply. It was, however, too indistinct to beunderstood.

"Could anything be stranger?" Jeanne asked herself. She knew that thevoice was that of a young man, or perhaps a boy. She felt that perhapsshe should proceed to vanish.

"But how can I?" she whispered, "and leave all this mystery unsolved?"

Oddly enough, the very next tune chosen by the musician was one of thosewild, rocketing gypsy dance tunes that Jeanne had ever foundirresistible.

Before she knew what she was about, she went gliding like some wildbewitching sprite across the flat surface of the roof. She was in thevery midst of that dance, leaping high and swinging wide as only shecould do, when with a suddenness that was appalling, the music ceased.

An ominous silence followed. Out of that silence came a small voice.

"Wha--where did you come from?"

"Ple--oh, please go on!" Jeanne entreated. "You wouldn't dash a beautifulvase on the floor; you would not strangle a canary; you would not stepupon a rose. You must not crush a beautiful dance in pieces!"

"But, ah--"

"Please!" Jeanne was not looking at the musician.

With a squeak and a scratch or two, the music began once more. This timethe dance was played perfectly to its end.

"Now!" breathed Jeanne as she sank down upon a stone parapet. "I ask you,where did _you_ come from--the moon, or just one of the stars?" She wasstaring at a handsome dark-eyed boy in his late teens. A violin wastucked under his arm.

"Neither," he answered shyly. "Up from a hole in the roof."

"But why are you playing here?" Jeanne demanded.

"I came--" there was a low chuckle. "I came here so I could play for thepigeons who roost under the tank there. They like it, I'm sure. Did youhear them cooing?"

"Yes. But why--" Jeanne hesitated, bewildered. "Why for the pigeons? Youplay divinely!"

"Thanks." He made a low bow. "I play well enough, I suppose. So do athousand others. That's the trouble. There is not room for us all, so Imust take to the house-tops."

"But how do you live?" Jeanne did not mean to go on, yet she could notstop.

"I play twice a week in a--a place where people eat, and--and drink."

"Is it a nice place?"

"Not too nice, but it is a nice five dollars a week they pay me. One mayeat and have his collars done for five a week. The janitor of thisbuilding lets me have a cubbyhole under the roof, and so--" he laughedagain. "I am handy to the pigeons. They appreciate my music, I am sure ofit."

"Don't!" Jeanne sprang up and stamped a foot. "Don't joke about art.It--it's not nice!"

"Oh!" the boy breathed, "I'm sorry."

"What's your name?" Jeanne demanded.

The boy murmured something that sounded like "Tomorrow."

"No!" Jeanne spoke more distinctly. "I said, what's your name?"

The boy too spoke more distinctly. Still the thing he said was to Jeannesimply "Tomorrow."

"I don't know," she exclaimed almost angrily, "whether it is today still,or whether we have got into tomorrow. My watch is in my room. What I'dlike to know is, what do your parents call you?"

"Tomorrow," the boy repeated, or so it sounded to Jeanne.

Then he laughed a merry laugh. "I'll spell it for you. T-U-M, Tum. That'smy first name. And the second is Morrow. I defy you to say it fastwithout making it 'tomorrow'!

"And that," he sighed, "is a very good name for me! It is always tomorrowthat good things are to happen. Then they never do."

"Tum Morrow," said Jeanne, "tomorrow at three will you have tea with me?"

"I surely will tomorrow," said Tum Morrow, "but where do I come?"

"Follow me with your eye until I vanish." Jeanne rose. "Tomorrow liftthat same trap door, climb down the ladder, then look straight ahead anddown. You will probably be looking at me in a very beautiful studio."

"Tomorrow," said Tum Morrow, "I'll be there."

"And tomorrow, Tum Morrow, may be your lucky day," Jeanne laughed as shewent dancing away.

Tomorrow came. So did Tum Morrow. Jeanne did not forget her appointment.She saw to it that water was hot for tea. She prepared a heaping plate ofthe most delicious sandwiches. Great heaps of nut meats, a bottle ofsalad-dressing and half a chicken went into their making.

"Tea!" Florence exclaimed. "That will be a feast!"

"And why not?" Jeanne demanded. "One who eats on five dollars a week andkeeps his collars clean in the bargain deserves a feast!"

The moods of the great artist were not, however, governed by afternoonappointments to tea. When Tum Morrow, having followed Jeanne'sinstructions, found himself upon the studio balcony, he did not speak,but sat quietly down upon the top step of the stair to wait, for there inthe center of the large studio, poised on a narrow, raised stand, wasJeanne.

Garbed in high red boots, short socks, skirts of mixed and gorgeous huesand a meager waist, wide open at the front, she stood with a brighttambourine held aloft, poised for a gypsy dancer.

To the right of her, working furiously, dashing a touch of color here,another there, stepping back for a look, then leaping at her canvasagain, was the painter, Marie Mabee.

Evidently Tum Morrow had seen nothing like this before, for he sat there,mouth wide open, staring. At that moment, so far as he was concerned,tomorrow might at any moment become today. He would never have known thedifference.

When at last Marie Mabee thrust her brushes, handles down, in the top ofa jug and said, "There!" Tum Morrow heaved such a prodigious sigh thatthe artist started, whirled about, stared for an instant, then demanded,"Where did you come from?"

Before the startled boy could find breath for reply, she exclaimed, "Oh,yes! I remember. Jeanne told me! Come right down! She has a feast allprepared for you."

She extended both hands as he reached the foot of the stairs. Tum tookthe hands. His eyes were only for Jeanne.

It was a jolly tea they had, Jeanne, the artist, and Tum. Tum's shynessat being in the presence of a great personage gradually passed away.Quite frankly at last he told his story. His music had been the gift ofhis mother. A talented woman, she had taught him from the age of three.When she could go no farther, she had employed a great teacher to helphim.

"They called me a prodigy." He sighed. "I never liked that very much. Iplayed at women's clubs and all sorts of luncheons and all the ladiesclapped their hands. Some of the ladies had kind faces--some of them," herepeated slowly. "I played only for those who had kind faces."

"But now," he ended rather abruptly, "my teacher is gone. My mother isgone. I am no longer a prodigy, nor am I a grown musician, so--"

"So you play for the pigeons on the roof!" Jeanne laughed a trifleuncertainly.

"And for angels," Tum replied, looking straight into her eyes. Jeanneflushed.

"What does he mean?" Miss Mabee asked, puzzled.

"That angels come down from the sky at night," Jeanne replied teasingly.

"But Miss Mabee," she demanded, "what does one do between the time he isa prodigy and when he is a man?"

"Oh, I--I don't know." Miss Mabee stirred her tea thoughtfully. "He justdoes the best he can, gets around among people and hopes something willhappen. And, bye and bye, something does happen. Then all is lovely.

"Excuse me!" She sprang to her feet. "There's the phone."

"But you?" said Tum, "you, Miss Jeanne, are a famous dancer--you mustbe."

"No." Jeanne was smili

ng. "I am only a dancing gypsy. Once, it is true, Idanced a light opera. And once, just once--" her eyes shone. "Once Idanced in that beautiful Opera House down by the river. That Opera Houseis closed now. What a pity! I danced in the _Juggler of Notre Dame_. Andthe people applauded. Oh, how they did applaud!

"But a gypsy--" her voice dropped. "With a gypsy it is different. Nothingwonderful lasts with a gypsy. So now--" she laughed a little, low laugh."Now I'm just a wild dancing bumble bee with invisible wings on my feet."

"Are you?" The boy's eyes shone with a sudden light. "Do you know this?"Taking up his violin, he began to play.

"What is it?" she demanded, enraptured.

"They call it 'Flight of the Bumble Bee.'"

"Play it again."

Tum played it again. Jeanne sat entranced.

"_Encore!_" she exclaimed.

Then, snatching up a thin gauzy shawl of iridescent silk, she wentleaping and whirling, flying across the room.

In the meantime, Miss Mabee, who had returned, stood in a cornerfascinated.

And it was truly worthy of her admiration. As a dancer, when the moodseized her Jeanne could be a spark, a flame, a gaudy, dartinghumming-bird, and now indeed she was a bee with invisible wings on herfeet.

"That," exclaimed the artist, "is a tiny masterpiece of music anddancing! It must be preserved. Others must know of it. We shall find atime and place. You shall see, my children."

Jeanne flushed with pleasure. Tum was silent, but deep in both theirhearts was the conviction that this was one of the truly large moments oftheir lives.

On the Yukon Trail

On the Yukon Trail Wings over England

Wings over England Johnny Longbow

Johnny Longbow Sally Scott of the WAVES

Sally Scott of the WAVES The Secret Mark

The Secret Mark Betty Leicester's Christmas

Betty Leicester's Christmas The Firebug

The Firebug Minnie Brown; or, The Gentle Girl

Minnie Brown; or, The Gentle Girl Jack the Hunchback: A Story of Adventure on the Coast of Maine

Jack the Hunchback: A Story of Adventure on the Coast of Maine The Silent Alarm

The Silent Alarm The Arrow of Fire

The Arrow of Fire The Magic Curtain

The Magic Curtain The Crystal Ball

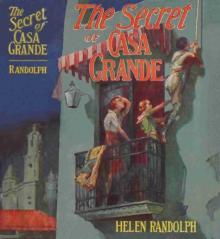

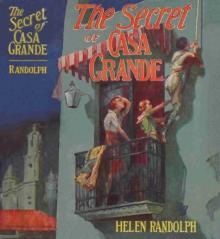

The Crystal Ball The Secret of Casa Grande

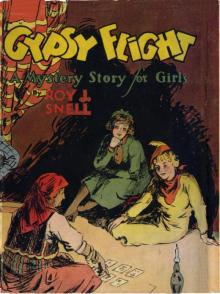

The Secret of Casa Grande Gypsy Flight

Gypsy Flight The Mystery of Carlitos

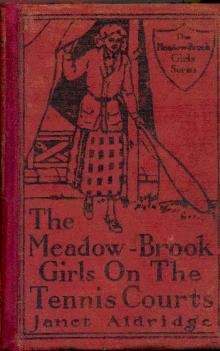

The Mystery of Carlitos The Meadow-Brook Girls on the Tennis Courts; Or, Winning Out in the Big Tournament

The Meadow-Brook Girls on the Tennis Courts; Or, Winning Out in the Big Tournament Witches Cove

Witches Cove Riddle of the Storm

Riddle of the Storm Forbidden Cargoes

Forbidden Cargoes Green Eyes

Green Eyes Sign of the Green Arrow

Sign of the Green Arrow The Red Lure

The Red Lure The Light Keepers: A Story of the United States Light-house Service

The Light Keepers: A Story of the United States Light-house Service A Ticket to Adventure

A Ticket to Adventure Helen in the Editor's Chair

Helen in the Editor's Chair Blue Envelope

Blue Envelope The Purple Flame

The Purple Flame Whispers at Dawn; Or, The Eye

Whispers at Dawn; Or, The Eye The Rope of Gold

The Rope of Gold Crossed Trails in Mexico

Crossed Trails in Mexico The Shadow Passes

The Shadow Passes Red Dynamite

Red Dynamite Blue Grass Seminary Girls on the Water

Blue Grass Seminary Girls on the Water The Cruise of the O Moo

The Cruise of the O Moo