- Home

- Roy J. Snell

Princess Sarah and Other Stories Page 4

Princess Sarah and Other Stories Read online

Page 4

CHAPTER IV

HER NEW HOME

At last Mr. Gray's affairs were all cleared up, and Sarah was about toleave dingy old Bridgehampton behind for ever to take up her new life inLondon, the great city of the world.

There were some very sad farewells to be made still; and Mrs. Stubbs wasa woman of very good feeling, and encouraged the child to go and saygood-bye to everybody who had been kind to her in the past.

"There is Mrs. Tracy," said Sarah on the last day. "She brought me allthat fruit and jam and the other things, Auntie."

"Oh, you must go and say good-bye to 'er, of course," returned Mrs.Stubbs; "and we must go and see your pore pa's grave, for 'eaven knowswhen you'll see it again."

"I should like to do that, please," said Sarah in a very low voice.

"Well, _I_ can't drag out all that way," remarked Mrs. Stubbs, who,being stout, was not good at walking exercise. "We'll have an opencarriage if nurse can get one; and nurse shall go too."

So Sarah went and said "good-bye" to her father's grave; and the wiseold nurse, after a minute spent beside it, drew Mrs. Stubbs away to theother side of the pretty churchyard to show her a curious tombstoneabout which she had been telling her as they drove along. So Sarah, fora few minutes, was left alone--free to kneel down and bid her farewellin peace.

It was a relief to the child to be alone, for Mrs. Stubbs, thoughmeaning to be kindness itself, was not a woman in whose presence it waspossible to grieve in comfort. Her remarks about "your pore pa"invariably had the effect of stifling any feeling of emotion which wasaroused in her childish heart.

She was very good. Sarah knew that she meant to be so.

"I'll try not to mind the difference, dear Father," she whispered to thebrown sods above his dear head. "It's all so different to you, sodifferent to when there was just you and I together. Nobody will everunderstand me like you, dear Daddy; but Auntie means to be very kind,and I'll try my hardest to grow up so that you'll love me better when wemeet again."

As she rose up, Mrs. Stubbs and the nurse were coming across the grassbetween the graves to fetch her. Mrs. Stubbs noticed the tears on hercheeks and still flooding her eyes.

"Nay, now, you mustn't fret, Sarah," she said kindly; "'e's better off,pore thing, than when he was 'ere, so you mustn't fret for 'im, there'sa good girl."

Sarah wiped her eyes, and turned to go away. She said nothing, for sheknew it was no use trying to make her aunt understand that her tears hadnot been so much for him as for herself. And Mrs. Stubbs stood for amoment looking down upon the mould, with its covering of brown,disjointed sods and its faded wreaths.

"Pore thing!" she murmured; "it's a sad end to 'ave. And he must 'avefelt leaving the little one badly 'fore he brought himself to write thatletter! Pore thing! Well, I'm not one to bear ill-will for what's pastand gone, and so beyond 'elp now; and I'll be as much a mother to Sarahas if 'im and me had always been the best of friends. 'E once said Iwas vulgar--and perhaps I am--it's vulgar to 'ave 'earts and such like,and he knows better now, pore thing! For I have a 'eart. Yes, and theQueen upon 'er throne, she has a 'eart, too, bless her."

There were tears on the good soul's cheeks as she turned to followSarah, whom she found at the gate waiting for her. By the time she hadreached the child she had wiped them, but Sarah saw that they had beenthere.

"Dear Auntie," she said. "He wasn't friends with you, but he knows howgood you are now,"--and then she flung her arms round her, and hervictory over her uncle's wife was complete.

"Sarah," she said, when they were nearly at the end of their journey,"you have never 'ad any playfellows, have you, dear?"

"Never, Auntie--not _real_ playfellows," Sarah answered, and flushing upwith joy at the anticipation of those who were in store for her.

"Well, I'd better warn you, Sarah--it may not be all sugar and honeytill you get used to them," said Mrs. Stubbs solemnly. "There's a gooddeal of give and take about children's ways; that is, if you want to geton peaceable. If you get a knock, you must just bear it withouttelling, or else you get called a 'tell-pie,' and treated according.It's what I've never encouraged, and I must do my children the justiceto say if they gets a knock they gives it back again, and there's nomore about it."

Thus Sarah was somewhat prepared for the darker side of her new life,though she gathered no true idea of the nest of young ruffians to whomshe was made known an hour later.

They came out with a rush to the door when the carriage stopped, andwelcomed their mother home again with a fluent and boisterous torrent ofjoy truly appalling to the little quiet and retiring Sarah, who was notaccustomed to the domestic manners of children of the Stubbs class.

"Ma, what have you brought me?"

"Is that Sarah, Ma? My, ain't she a littl'un!"

"Ma, Mary was late this morning. Yes, and our kao-kao was burnt--I toldher I should tell you."

"Pa slapped Johnnie last night, because he wouldn't be washed to comedown to dessert."

"And Flossie has torn her best frock."

"And May----"

"Hush! Be quiet, children!" exclaimed Mrs. Stubbs, holding her hands toher ears. "'Pon my word, you're like a lot of young savages. MissClark can't have taken much care of you whilst I've bin away. Really,you're enough to frighten Sarah out of her senses. This is your cousinSarah. She's going to live 'ere in future, so come and say ''Ow d'yedo?' to her nicely."

Thus bidden, the young Stubbses all turned their attention on their newcousin, and said their greeting and shook hands with various kinds ofmanner.

There was May, aged fourteen, a very consequential young person, with aninclination to be short and stout, like her mother, and had her nicefair hair plaited into a tail behind and tied with a bunch of mauveribbon, worn with a white frock in memory of the uncle by marriage whomshe had never seen.

"How d'you do, Cousin Sarah?" she said, with a fine-lady air whichpetrified poor Sarah, who thought that and her cousin's earrings andwatch-chain the finest things she had ever beheld about any human beingbefore. Then there came the redoubtable Flossie, who had torn her bestfrock, and was twelve and a half. Flossie, who was nearly as big asMay, came forward with a giggle, and said "How----" and went off intofits of laughter at some private joke of her own.

"I'm ashamed of you, Flossie," cried Mrs. Stubbs sharply; "shake 'andswith your cousin Sarah at once. Ah! this is Lily--Lily's five and a'alf, Sarah--she's the baby."

Then there was Tom, the eldest boy, who gripped hold of Sarah's hand andwrung it until she could have shrieked with the pain, but, taking it asan expression of kindness and welcome, she bore it bravely and looked athim with a smiling face; she knew better afterwards.

After Tom came the twins, Minnie and the Johnnie who had been slappedthe day before; and last of all, Janey, the prettiest, and Sarah fanciedthe sweetest, of them all. Janey was seven, or, as she said herself,nearly eight.

"I suppose," said Mrs. Stubbs, addressing herself to Flossie, "that yourpa 'asn't got 'ome yet?"

"No, Ma, not yet," returned Flossie.

But, presently, when Mrs. Stubbs had changed her dress for a garmentsuch as Sarah had never beheld before, and which May told her was atea-gown, and was enjoying a cup of sweet-smelling tea in the large andshady drawing-room--to Sarah a perfect dream of beauty--he came! Camewith a bustle and noise like a tempest, and caught his stout wife roundthe waist, with a "Hulloa, old woman, it's a sight for sore eyes to seeyou 'ome again!"

Sarah had determined to be surprised at nothing, but her Uncle Stubbswas altogether too much for her resolution. In apologising to herselfafterwards, she said she was obliged to stare.

"And where's the little lass?" Mr. Stubbs asked when he had kissed hiswife. "Oh, there! Well, aren't you going to speak to your uncle, eh?"

"Yes, Uncle," said Sarah shyly.

He drew her nearer to him, and turned her face to the light.

"Like her dear ma," put in Mrs.

Stubbs.

"Yes," said Mr. Stubbs shortly.

"Not like her pa at all," Mrs. Stubbs persisted.

"No!" more shortly still; then, after a pause, "I 'ope you'll be a goodgal, Sarah, and remember, though your father and me wasn't friends, yet,as long as I've a 'ome to call my own, you're welcome to a shelter init. Your mother was my favourite sister, and though she turned 'er backon me, I'll never do that on you, never."

"Father knows better now, Uncle," said the child, with an effort; "heknows how good you and Auntie are to me. You'd be friends now, wouldn'tyou?" earnestly.

"I don't know--I don't know at all," replied Mr. Stubbs shortly; then,struck by the pleading look on the child's wistful face, added gruffly,"I suppose we should; any way, I hope so."

At this point Mrs. Stubbs broke in,--

"Any way, it's no fault of Sarah's that we wasn't all the very best offriends, Stubbs; and Sarah and me's real fond of one another already,aren't we, Sarah? So say no more about it; what's past and gone isbeyond 'elp. Flossie, you can take Sarah upstairs now. It's justsix--time for your tea. Be sure she gets a good tea."

On the Yukon Trail

On the Yukon Trail Wings over England

Wings over England Johnny Longbow

Johnny Longbow Sally Scott of the WAVES

Sally Scott of the WAVES The Secret Mark

The Secret Mark Betty Leicester's Christmas

Betty Leicester's Christmas The Firebug

The Firebug Minnie Brown; or, The Gentle Girl

Minnie Brown; or, The Gentle Girl Jack the Hunchback: A Story of Adventure on the Coast of Maine

Jack the Hunchback: A Story of Adventure on the Coast of Maine The Silent Alarm

The Silent Alarm The Arrow of Fire

The Arrow of Fire The Magic Curtain

The Magic Curtain The Crystal Ball

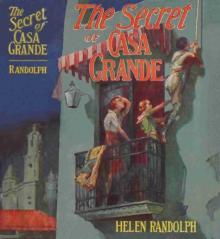

The Crystal Ball The Secret of Casa Grande

The Secret of Casa Grande Gypsy Flight

Gypsy Flight The Mystery of Carlitos

The Mystery of Carlitos The Meadow-Brook Girls on the Tennis Courts; Or, Winning Out in the Big Tournament

The Meadow-Brook Girls on the Tennis Courts; Or, Winning Out in the Big Tournament Witches Cove

Witches Cove Riddle of the Storm

Riddle of the Storm Forbidden Cargoes

Forbidden Cargoes Green Eyes

Green Eyes Sign of the Green Arrow

Sign of the Green Arrow The Red Lure

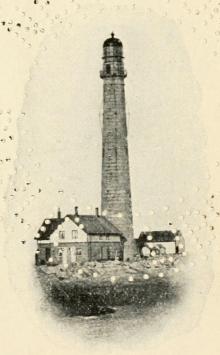

The Red Lure The Light Keepers: A Story of the United States Light-house Service

The Light Keepers: A Story of the United States Light-house Service A Ticket to Adventure

A Ticket to Adventure Helen in the Editor's Chair

Helen in the Editor's Chair Blue Envelope

Blue Envelope The Purple Flame

The Purple Flame Whispers at Dawn; Or, The Eye

Whispers at Dawn; Or, The Eye The Rope of Gold

The Rope of Gold Crossed Trails in Mexico

Crossed Trails in Mexico The Shadow Passes

The Shadow Passes Red Dynamite

Red Dynamite Blue Grass Seminary Girls on the Water

Blue Grass Seminary Girls on the Water The Cruise of the O Moo

The Cruise of the O Moo